Alex Padilla's Housing Plan is Tired and Outdated

But it is not an outlier in Democratic thought

Housing is too expensive. Whether it’s renting or owning, basically everyone across the political spectrum can agree on this basic fact. Differences arise when you ask, “why is housing expensive?” and “what can be done to fix it?”

Parts of the political Right will tell you that the problem is immigrants coming into housing markets and pushing up the prices by increasing demand.

Parts of the political Left will tell you that the problem is greedy landlords, “luxury” apartments, and private equity companies buying controlling stakes in the housing market, “controlling” in this case apparently meaning 2% of all single family homes and 2% of all rental properties.

For people affiliated with the YIMBY movement, which spans the ideological spectrum, the problem is multifaceted and complex. But the general consensus will point to regulations that make it hard if not impossible for both the public and private sectors to build. Zoning requirements that make it illegal to build homes in the quantity that are needed to tackle supply shortages. Inclusionary zoning mandates that allow builders to construct housing units, but only in ways that cause them to effectively lose money in the process. Permitting processes that allow unrepresentative minorities to slow down the process of building needed homes. These all share a portion of the blame for why America has failed to build millions of units needed to house its population.

But what does Alex Padilla, the senior senator from California, think is the cause and solution to the housing issue?

Back in 2024, he was given the opportunity to state his position on this issue. In the waning days of congress, a coalition of advocacy groups including The New Democrat Coalition, YIMBY Action, The National Low Income Housing Association, The National Apartment Association, and The Center for New Liberalism all pushed to try to pass the Yes In My Backyard or YIMBY Act (H.R.3507) through Congress. This was a bill with a bipartisan coalition of cosponsors, intended to help reduce the regulatory burdens that make it hard to build housing.

If you were a Californian who reached out to your elected representatives to push them to support the YIMBY Act, you likely received this letter from the office of Senator Alex Padilla sometime in late January, notably after the 118th Congress had ended and the Trump Administration had been inaugurated.

Dear [Constituent],

Thank you for writing to share your concerns regarding the affordable housing and homelessness crisis. I appreciate hearing from you.

I strongly believe that everyone deserves a safe, stable, and affordable place to call home. The United States has a shortage of 7.3 million affordable homes available to low-income renters, and more than 185,000 people experience homelessness in California each night. Addressing the affordable housing and homelessness crisis has been one of my top priorities as your Senator.

That is why I was proud to introduce the “Housing for All Act” (S. 2701), a comprehensive bill to ensure every American has the dignity and security of housing. This bill would have invested billions of dollars in proven programs that help alleviate the affordable housing shortage, including the National Housing Trust Fund, the HOME Investment Partnerships program, the Section 202 Supportive Housing for the Elderly program, and the Section 811 Supportive Housing for People with Disabilities. S. 2701 would have targeted the homelessness crisis by providing significant funding for Housing Choice Vouchers, Project-Based Rental Assistance, the Emergency Solutions Grant program, and Continuums of Care. This bill would have also supported innovative, locally developed approaches, such as investments in hotel and motel conversions and safe parking programs. This bill did not pass the Senate in the 118th Congress but I plan to reintroduce the bill this Congress.

Furthermore, I proudly voted for the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (Public Law 117-2), which was signed into law by President Biden on March 11, 2021. This law provided California with an additional $250 million in federal funding for the Emergency Housing Vouchers program, which is made available to public housing agencies to assist those who are experiencing homelessness, those at risk of homelessness, and those who have recently become homeless.

Supporting policies that allow all Americans to attain stable housing is critical. Please know that I will continue working to ensure that all Americans have access to affordable housing.

Once again, thank you for writing. Should you have any other questions or comments, please call my Washington, D.C. office at (202) 224-3553 or visit my website at padilla.senate.gov. You can also follow me on Facebook, and Twitter, and you can sign up for my email newsletter at padilla.senate.gov/newsletter.

Sincerely,

Alex Padilla

United States Senator

There are a few things of note in this letter that seem worth highlighting. First, the letter makes no mention whatsoever about the YIMBY Act, instead it is seemingly a generic form letter sent to constituents inquiring about housing issues. Second, it makes no mention of efforts to reduce regulatory burden. Third, the term “affordable” makes a frequent appearance. This is a common tactic used in housing discourse by those who want to look like they’re trying to increase supply while opposing the building of market rate housing, i.e. the type of housing that most Americans live in. Finally, there is the focus on Padilla’s own Housing for All Act, which seeks to ensure access to housing by “invest[ing] billions of dollars,” “providing significant funding,” and “investments in hotel and motel conversions and safe parking programs.” In his own words, Padilla wants to fix the housing issue by throwing money at it, an approach that has been spectacularly unsuccessful in Padilla’s hometown of Los Angeles.

Since Padilla seems to be positioning the Housing for All Act as the superior piece of housing legislation over the unmentioned YIMBY Act, it seems only fitting to compare them to see what they say about the people writing them. Neither bill is especially long or hard to read, so it may be worth skimming them.

The YIMBY Act is, frankly, a fairly modest bill in the grand scheme of things. The bill only has one major provision which requires that recipients of the Community Development Block Grant Program submit a report every 5 years on what policy changes they have made or are planning to make to make housing construction easier and cheaper. These policies are the standard set of reforms that will sound familiar to anyone who has any experience with YIMBY politics and the laws that govern what can be built where. Things like removing parking requirements, reducing minimum lot sizes, relaxing height restrictions, and so on. Notably, the law does not mandate that grant recipients make any sort of policy changes to continue receiving their allocated funds. They just need to submit a report on their housing policy and how, if at all, they are planning to change it. In short, it is a disclosure and transparency requirement. Moreover, the Community Development Block Grant Program is not a particularly big program in the grand scheme of things, having disbursed about $3.3b in 2023, a sizeable chunk of money to your average voter, but paltry in comparison to all the other ways the federal government disburses money to states and localities, such as the $24b spent on disaster relief, $48b on Highways, and $616b on Medicaid.

So if the law targets a small program and doesn’t even mandate any policy change, why the hoopla over trying to get it passed? The answer may be that the YIMBY Act, if passed, would have represented an important messaging victory in housing politics. The bill clearly lays out that burdensome regulations are an obstacle to building needed housing which states and localities should strive to lessen in order to allow housing to be built faster and cheaper than it currently is. It sets out the principle that, in order to build the homes needed to ensure that everyone can live somewhere, governments need to stop loading every project up with endless rules, hearings, costs, process, and procedure.

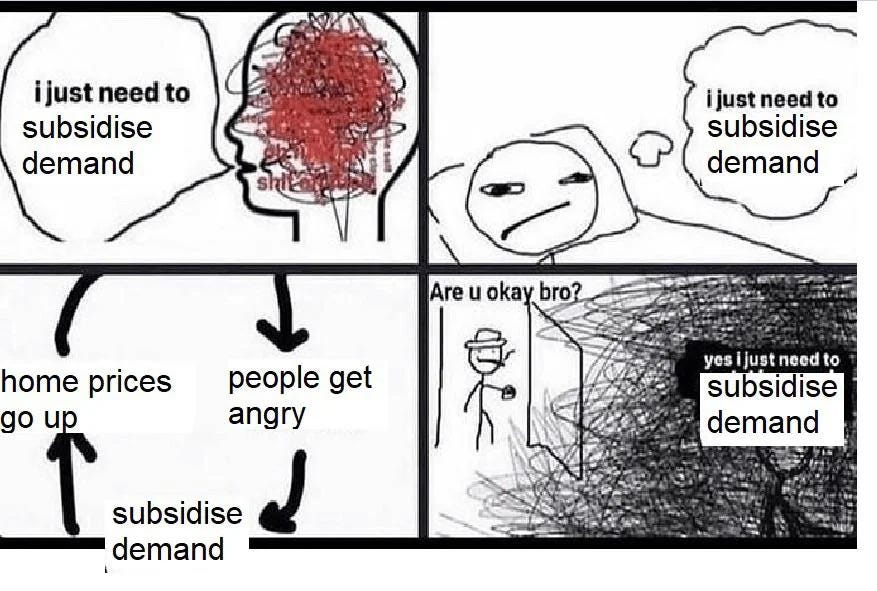

Contrast this with Padilla’s bill, which reads like a parody of everything wrong about how Democrats approach the issues of governance. It sets aside $10m annually to establish a racial equity commission for housing issues. There is an appropriation of an unspecified amount to create a program to provide technical assistance to help states understand how to secure federal funding for housing projects. This is part of a proud Democratic tradition of acting as if the problem with any bureaucracy is not that there’s too many rules, but rather that there’s not enough bureaucrats. The only mention of parking is not in any sort of effort to reduce parking requirements to allow more houses to be built on the finite amount of land that any project has access to, but a plan to spend $25m on safe parking programs of the type tried in San Francisco, which cost an eye watering $140k per year per vehicle and closed after 3 years. And of course, there’s no mention whatsoever about any sort of regulation restricting what can be built, where it can be built, or how it can be built, just more proposals to spend north of $100b. In the eyes of the drafters of the Housing for All Act, the solution to the housing problem has nothing to do with regulation and everything to do with insufficient money being thrown at renters and new construction projects, the classic “just subsidize demand” solution.

It’s perhaps a little unfair to single out the HFAA in this way. As a bill originally proposed in early 2022 (S.3788) and likely conceived sometime in 2021, it is just one of many Democratic proposals of the era that sought to dump billions of dollars into the American economy in the hopes that it could increased investment would spur growth, even while adding on more and more hooks and restrictions onto said investments. Essentially, it was just another “Everything Bagel” initiative that predominated in that era.

What is more galling is the continued insistence that this type of politics is still worth pursuing in 2025, when it has clearly shown to not work. The Biden Administration got a $42b allocation to build out rural broadband as part of the 2021 Infrastructure Act, which produced zero broadband connections by the end of his term. $7.5b were appropriated for electric vehicle chargers. At the start of this year, that program had resulted in less than 50 chargers actually getting built. This style of politics, where the federal government declares it intends to spend massive quantities to fix this or that issue, loads on all sorts of ancillary goals to projects it seeks to fund, spends a fraction of what was allocated, and gets a negative return on the political capital spent, has been an abject failure. What is needed is an approach that thinks not in billions allocated, but in bottlenecks eliminated.

Though modest in the requirements it places and the effect it is likely to have, the YIMBY Act was a move in this direction of recognizing that in order for the government to actually deliver on the laudable goal of increasing housing supply, it needs to take a step back and think about how to get out its own way and recognize that it doesn’t matter how much gas (or electricity) you put in a car, if the engine is broken, you won’t get anywhere.