Money Talks, But It Doesn’t Always Win

A look at campaign donations in San Francisco's competitive board of supervisors races.

With the 2024 San Francisco elections closed, the victors inaugurated, and the losers banished to the deepest pits of Tartarus1, now is a good time to take a look back and see what lessons can be taken from the election. Much has already been made about the city’s apparent turn against the political left and the incumbent political class with the election of Daniel Lurie, Danny Sauter, and Bilal Mahmood.

But one interesting aspect to take a look at is the role that money played in the election. Beyond the role that money played in Daniel Lurie massively outspending his rivals in the mayoral race, what role did money play in the election of the board of supervisors? Money obviously comes in handy when it comes to buying ads, paying staffers, and sending mailers. But in the era of Act Blue and small dollar donations, money can also be a good gauge of public sentiment beyond what’s told by votes alone. Voting, after all, is pretty cheap, especially when San Francisco’s universal mail-in ballot system has removed the need to even wait in line in order to make one’s voice heard. It’s a good way to find out how many people like a given candidate, but it doesn’t necessarily tell us much about how strongly they like a candidate.

Donations speak in a different way. You have to really like a candidate or really hate one of their opponents in order to part with up to $5002. Moreover where donations come from can also be instructive, a candidate who brings in a ton of donations may seem to have a good base of support with which to win an election, but if most of that money is coming from outside either district or even outside the city, then that support may not translate to votes as well as it would for a candidate who pulls most of their donations from within their district.

Considering that, let’s take a look at the various San Francisco Board of Supervisors races and what the donations to them can tell us about San Francisco politics.3

District 1

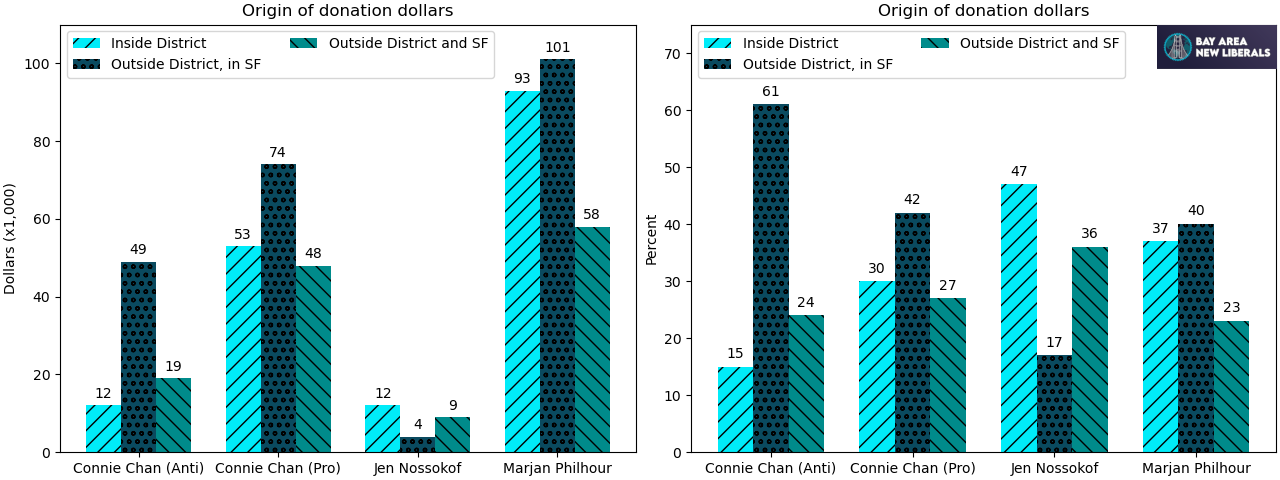

Looking at the district centered around the Richmond District, it stands out just how much money was arrayed against the eventual winner, Connie Chan, both in the form of a Grow SF sponsored committee against her and the monstrous war chest raised by her main opponent, Marjan Philhour.

This is somewhat misleading as it doesn’t reflect the $1,000,000 of spending in the last month of the election by a Chan supporting union independent expenditure committee.

District 3

Moving East to the district with Chinatown, Fisherman’s Wharf, North Beach, Ghirardelli Square, and most of the rest of San Francisco’s tourist destinations, we see one potential data point in support of the thesis that candidates with a greater share of in-district donations win elections when we look at the distribution of donation dollars given to the winner, Danny Sauter. While Danny and Sharon Lai, the second place finisher, managed to raise similar amounts of money overall, Danny, who had run for the same seat in 2020 and had spent more than a decade working in Chinatown and North Beach, pulled much more money from within District 3, in both absolute terms and as a percentage of his overall funds.

District 5

Heading into the most high profile race of the election, we see some absolutely insane fundraising numbers. $350,000 for incumbent Supervisor Dean Preston. $270,000 for a GrowSF backed anti-Preston committee. $230,000 for the winner, Bilal Mahmood. District 5 was an expensive election, being the only race seeing more than a million dollars raised by all the candidates.

More striking perhaps is just how much of the money came from within the district. In spite of Dean’s claims that opposition to him was funded by shadowy cabals of outsider Republican billionaires, both the Grow and Bilal campaigns raised a greater share of their money from inside District 5 than Dean did. And if any major candidate could be accused of being funded by outside money, it would probably be Dean, considering that he had the greatest share of money coming from outside San Francisco, likely thanks to an endorsement by Bernie Sanders and Dean’s stature as one of the most high profile elected members of the Democratic Socialists of America.

District 7

From a donations perspective, the District 7 election takes the record for the least expensive of the 2024 BoS cycle. While the combined candidates and committees in every other district raised at least half a million dollars, the candidates in District 7 barely cracked $350,000. This may be because the incumbent and winner, Myrna Melgar, was not closely aligned with either the Progressive or moderate camp of SF city politics and the main issue of the campaign, the closure of the Great Highway to cars and its conversion into a park, felt fairly parochial in comparison to city spanning issues of crime, housing, and drugs that most of the other Board elections were fought on. This hyperlocal facet of the race can be seen in the higher than normal share of in-district donations to the candidates.

District 9

Of all the board elections in the 2024 cycle, District 9 was the biggest blowout, with the winning candidate, Jackie Fielder, beating Trevor Chandler by a 20-point margin. Interestingly, the 3rd place candidate, Roberto Hernandez, who was the odds-on favorite going into the election off the back of his lifetime of involvement in various community organizations in the Mission, received the greatest share of support from donors outside of San Francisco of any major candidate in a Board of Supervisors race. A good reminder that expectations don’t always align with reality.

District 11

rapping up at the bottom of the city, we come to the closest race of the election, in which Chyanne Chen managed to beat Michael Lai by 190 votes or a less than 1% margin of victory. One noteworthy feature of this race is the share of donations from non-San Franciscan donors. All the candidates in the race had about 2/5ths of their campaign donations coming from outside of San Francisco, compared to an average of about 25% for the candidates in the remaining five districts. One might think that this is because District 11 is one of three districts that touch San Francisco’s southern border and that the majority of the non-SF donations to the D11 campaigns came from Daly City and Brisbane residents hoping to influence the politics of their domineering northern neighbor. Surprisingly, less than $10,000 of the $147,000 worth of non-San Franciscan dollars came from Daly City and Brisbane ZIP codes. Rather outside donations to the D11 came from all across the Bay Area.

The other thing that stands out is Michael Lai’s monstrous fundraising lead, having raised almost as much as all of his opponents combined. However, this is somewhat deceiving as Chyanne Chen received $600,000 in support from a pair of labor union aligned independent expenditure committees late in the race, similar to Connie Chan. Apparently labor unions like supporting female candidates with the initials C.C.

Going through all the Board of Supervisor elections, there’s obviously a lot of interesting factoid and random data points that you can tease out between candidates in and from individual candidates’ fundraising hauls, but do any patterns emerge when looking at the whole? Let’s answer that question with an series of questions about the role of money and see if anything definitive shakes out:

Does the candidate that raises the most money win?

No. In every race aside from D9, the winner was outraised by another candidate that they ultimately beat.

Does the candidate who raises the most money from within their district win?

Again, no. Marjan Philhour, Dean Preston, Matt Boschetto, and Ernest Jones all raised significantly more money within their district than any of their rivals while still losing, sometimes not even coming in second.

Does the candidate with the greatest share of their donations originating from within their district win?

Shockingly, no. Danny Sauter, Bilal Mahmood, and Mynar Melgar all managed to get a larger percentage of their funds from their district than their opponents while winning. But Marjan Philhour, Roberto Hernandez, and Ernest Jones all managed the same feat and ended up losing, the latter two quite badly.

Well what about the share of donations within San Francisco?

Still no. Sauter, Mahmood, and Fielder all won while getting the highest percent of in-city donations in their races. But this didn’t hold in the other three races.

So it would seem that, despite the views of some on the left that elections in America are decided on the question of who has the most money at their disposal, in the context of San Francisco Supervisorial elections, fundraising skill doesn’t predict the eventual winner of the election more than half the time.

In a stunning turn of events, the world is complicated and you can’t divine the future from a single variable.

Presumably

All the major BoS campaigns voluntarily limited themselves to a $500 per person contribution limit in order to gain access to donation match offered by the city.

All the donation data was sourced from sfethics.org. Donation dollars were tied to zip codes which do not cleanly map onto supervisorial districts, but they are at least geographically proximate enough that an “Inside district” donation can be safely assumed to be made by someone who lives in or at least close to the district. The data in question also only shows named donors. Independent expenditure committees, which played a major role in several races, mostly didn’t disclose their donors and as such aren’t displayed in our charts. If you’re interested in the data and code used to make the charts in this piece, feel free to reach out.